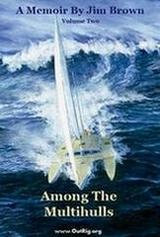

The NEXT Last Chapter – An Afterword To AMONG THE MULTIHULLS

by Jim Brown

The original, working title for my story “Among the Multihulls” was “Wind Against Current.” It was to signify the old multihull/monohull schism, the winds of change blowing against the inexorable flow of tradition, a condition which always makes waves. But because the book is distributed mainly on the Web, it was felt that the title should contain the word “multihull.” I dislike that techno babble term, but at least the internet search engines can find the book. And besides, over time wind causes current, so during the last fifty years the stream has been turned. Finally, tradition is flowing with the wind, and multihulls now encounter smoother seas…

My memoir transpired during that fifty year period, from about 1946, when Woody Brown was in the process of conceiving the first modern multihull, to 1996, when Jo Anna and I made our last cruise (to Cuba) in SCRIMSHAW. But Volume One of the book wasn’t actually released until 2010, so it’s going on fifteen years since the story stops. A lot has happened in the in that time, and it seems that by now, 2014, the readers deserve a bit of updating.

My memoir transpired during that fifty year period, from about 1946, when Woody Brown was in the process of conceiving the first modern multihull, to 1996, when Jo Anna and I made our last cruise (to Cuba) in SCRIMSHAW. But Volume One of the book wasn’t actually released until 2010, so it’s going on fifteen years since the story stops. A lot has happened in the in that time, and it seems that by now, 2014, the readers deserve a bit of updating.

So, below I will include my original abstract of each chapter, and follow that with something of that chapter’s aftermath. Here’s hoping that this hindsight/foresight vantage will inform the reader – and most of all the writer — of some not-yet-quite-identified conclusions.

The Freudian meaning of boats. Drawing the plans, starting SCRIMSHAW, planking parties. Multihull events of late 60s. Writing Construction manual, launching SCRIMSHAW, collision with Commodore, ramming restaurant, BACCHANAL wins TransPac, Friends take over author’s blooming design business, Browns take off for Panama in SCRIMSHAW, a family crew with no destination and no plans to return to California.

Author’s update to Chapter 1:

Some time after Walt Glaser made those Freudian remarks that opened Volume 1 (“A man builds a boat … to make up for the fact that he can’t build a baby”), he inherited big money. But perhaps because of his propensity to blow it on hedonism, he lost it all in court to his relations. Together with his mischievous pet rat Abigail he lived aboard his SALLY LIGHTFOOT trimaran for many years, the wizened bard and gut-splitting cynic of Santa Cruz harbor. His rat delighted in stealing anything it could carry, especially if Walt was handling something small at the time. When approaching Walt’s boat at dockside, I once heard coming from his cabin the desperate cry, “Give me back my Zantak, you dirty rat.”

Sadly, Walt was so discerning of human behavior that it ate him up, and he died in 2008 of post-polio syndrome and his grudges, a destitute, embittered ward of the State.

I surely learned a lot from old Walt, including those most valuable lessons on how not to be, but I miss him. We had some great laughs together, and he taught me to respect what I was doing with my boats. His life seems now to stand as an extreme example of Henry Beston’s balance between “splendor and travail.” As part of our Outrig Project, Walt Glaser’s trimaran designs and writings will be archived at the Mariners Museum, Newport News, Virginia, where the collections of several other multihull luminaries now reside.

Schooner bumming. Author meets his most formative mentor, an early multihull pioneer. Together they voyage from Miami to Colombia in 1956 with a very game young woman in their crew. This mentor and woman disappear from the story for the next thirty years, but the author resolves to pursue a nautical life on his own. Obsessively keeping this youthful resolution is the theme of the next nine chapters.

I still often think of Wolfgang Kraker von Schwarzenfeld, and the profound influence he had on my life. He introduced me to the very notion of design, that anyone can do it. And he embodied the freedom that comes from going out into the ocean in order to change one’s geographical location and cultural immersion. Wolf showed me how such changes come so clearly into contrast when separated by time at sea.

I mentioned in this chapter that Wolf and I lost track of each other for some thirty years, and then (in Chapter 15) we connected again. Typical of the way in which people seem to fade in and out of each other’s lives, Wolf and I have again lost contact. However, I once learned he had become renowned as a sculptor. So again, “Wolfie, if you are reading this, where are you?”

Becoming a disciple of Arthur Piver. the Father of the Modern Trimaran. Story of author’s commitment to multihulls; countercultural schism between multis and monos begins. Building JUANA, marriage to Jo Anna, departure for points south with Jo Anna 5 ½ months pregnant carrying their firstborn Steven.

Dixie Piver, youngest of the two daughters of Florence and Arthur Piver, called me some time in the early 90s to explain that she and her sister Nancy had helped their mother move from the family home to a care facility, and they were in the process of preparing the place for sale. Jo Anna and I had known the Piver daughters in their adolescence, and now Dixie said, “Mother saved everything. All that old trimaran stuff, including his design drawings, correspondence, accounts and books – cases of Father’s books – are all in mint condition, and we can’t find anyone in San Francisco who can take the stuff. There are something like 72 file boxes of it, and we hate to just haul them to the land fill.”

“Hang on, Dixie,” I pleaded. “Give me a few days and I’ll call you back.”

That phone call was the initiation of the multihull history collection at the Mariners Museum, Newport News, Virginia. With the cooperation of Mr. Lyles Forbes, curator, we formed the Outrig Project for gathering the personal memorabilia, design drawings, models and on-camera interviews of over twenty multihull luminaries. Recently, the Museum has also received artifacts from the 2013 Americas Cup vessels. Moreover, the initial steps are being taken to utilize this video material – and much more – in the preparation of a documentary for national broadcast on the advent of modern multihulls.

As related in this chapter, Arthur Piver disappeared at sea in 1968; no trace was ever found of man or boat. My world – and that of many others especially his daughters’ – has never quite recovered from that loss, for Piver was a true visionary. He told us in no uncertain terms, “…all sailing speed records will be held by multihulls.” When watching the 2013 Americas Cup contest, I could not help remembering that it was in those very same waters of San Francisco Bay that Piver’s early multihulls were developed. We thought it revolutionary when those early vessels achieved speeds in the mid teens, and now the huge, hydrofoil-borne catamarans are achieving fifty mph. This is only one example of the enormous technical advances made for multihulls in the ensuing fifty years.

First modern seafaring trimaran. Losing and then recovering JUANA at Todos Santos, narrowly escaping destruction in a hurricane by beaching the boat at Cape San Lucas, rescue by Mexicans, Empathetic relations with Mexican fisherfolk, birth of firstborn son Steven.

Since nearly losing JUANA twice in two days, first at Todos Santos and then at Cape San Lucas back in 1959, Baja has changed dramatically. This drama is nowhere more evident than at San Lucas, now known as the mega resort complex “Cabo.” Then nothing more than a dilapidated tuna cannery with a thatch-and-wattle village, the place now sports a tight, man-made harbor, several fine hotels, even golf courses in the desert kept green with desalinated seawater) and a lively little town.

I have been back to Cabo twice since our first visit in JUANA. There I met again with Mr. Luis Bulnes, formerly the manager of the cannery and our savior in 1959 but later the proprietor of the best hotel at Cabo. I say best for its location. It snuggles up against the rocky spine of the Cape itself on its seaward side, completely away from the bustle of the town and facing south toward Polynesia and infinity.

Luis and I enjoyed a fine reunion, and at the hotel bar he told me of a guest who once arrived (unlike most tourists) in a business suit. After checking in, the guest asked if he might leave his jacket, shoes and luggage in the lobby for a while before going to his room. Luis watched him step out onto the beach, roll up his trousers and stand on the brink of the surf – the brink of the world – alternately staring at the sea and the sky for a long, long time. When the man returned, Luis could not resist asking him, “What was that all about?”

The man replied, “I am an Apollo astronaut, and have seen the Earth from space a lot. Looking down from orbit, it has always seemed to me that this must be the most beautiful place on the Planet, so I resolved to come and see it up close. I am so very pleased to be here.”

Several iterations of Piver’s seminal designs, such as the 24-foot NUGGET, the 30’ NIMBLE and the 35’ LODESTAR trimaran, are still afloat. Our Nugget, JUANA (featured in this chapter) may still be also. She was sold first in 1963 to Charlie Crocker, then to John Gunnels, then to Jo Hudson, then back to me, then to Dean Taylor, and then to… Something like that; I can’t remember. She was last known to be in Northern California, and I often wonder if she is still alive. If we could find her, and if she hasn’t crumbled into oatmeal, there might be a place for her at The Mariners Museum. So, dear old JUANA, first modern trimaran to go to sea, if you’re reading this, where are you?

Multihull mania begins. Retrieving JUANA from Mexico. Voyage to Manzanillo, hitching ride for boat to San Diego aboard a tuna clipper. Moving to Big Sur. Pivotal multihull personalities. Stories of launchings and shipwrecks of the author’s designs. Conflict with the yachting establishment. Inauspicious beginning of author’s design career.

This chapter introduced Don McQueen and Jo Hudson, both of whom still figure strongly in my here-and –now…

McQueen still stands as the finest teacher in my experience, untiringly willing to share his comprehensive grasp of the tangible world. He sold the early Piver 40 SOUTH COAST that we built together in the early 60s, and as far as I know the boat is still sound but has never left California. Don was surely not the right guy for multihulls, because the boat of his life became a 50-foot, very shippy, steel motorsailer. After cruising for a week with Don and his wife Mieka (both of them consummate mariners), aboard their SUSAN GAEL in maritime British Columbia, I came fully to understand why they have chosen such a vessel for their junkets between Seattle and Alaska. The sailing isn’t great in those waters, and, unless especially built for it, multihulls are not great in the cold; too lightly built to be thermally resistant, and too much surface area for their volume. Many multihulls have cruised Alaska and the like, but they are happier in warmer water and steadier wind.

Hudson, on the other hand, has owned ten trimarans, seven of my design (counting four Windriders). We have sailed most of them together, hither and yon, but Jo has sailed a lot more than I have. We are both somewhat restrained these days by our “worn parts,” but we still get down to some serious messing about (we say screwing around) in multihulls.

Maybe this is where I should say something about the multihull life style. It’s no hooey. Neither should it be diminished by the term “Style.” It’s more like the multihull mentality, the modus de vida or manner in which one (meaning one of us convicted multihullists) invests his or her life. Each of us has a heartfelt story of the gains and losses from that investment, our private focus on the sailor’s life and how that lens has been adjusted over time.

For example, when I began schoonerbumming at age 20, the initial purpose was commercial. That is, I bought-in to Mike Burke’s vision of buying up old windjammers, ones that were destined for neglect and demise, and putting them to work running sailing/diving charters. The purpose was dual; to sustain ourselves and to keep the boats alive. In the process, the vessels inserted me into my first exposure to foreign cultures, first the Bahamas, where their English made things easy but the place was “foreign nonetheless. Then Cuba, where Spanish introduced me to its special level of consciousness – another life – and then to Mexico, where the influence of the ancient Aztec and Maya added real depth to otherwise shallow harbors.

So a boat, to me at the time, was first a meal ticket and then a time machine. Why live always in one time and place when you can live in many of both? And why own a boat that the owner must sustain, when a boat can sustain its owner?

Unless, that is, a non-commercial craft can impart the foreign culture aspect without the need to carry passengers for hire. This leads to the cruising focus, which for me led to designing boats for cruising, and these, if intended for serious, long-term, live-aboard, passagemaking cruising, are actually highly specialized workboats. If multihulls, these are fun to design because they demand lots of careful compromise, and when selling plans to owner-builders of such craft, the designer is thrust into a world of frustrated, exciting adventurous escapist clients many of whom become friends. Now, that’s something more than life “style.”

All of this made recreational day sailing, and especially yacht racing, seem frivolous to me. As I grew older, however, I realized that serious ocean cruising is not for everyone, It has a long, slow learning curve, and somewhere along that curve it is quite possible for the student to have his or her mind fried – just by dealing with the ocean day and night.

So it was that after forty years of cruising focus, I came back into little multihulls, like the Windriders (Chapter 20). They offer some relief from the heavy responsibility of seafaring, and they are just as challenging to design especially when designing for production, and they bring the joys of sailing to many who would otherwise miss out. Racing in small boats, it turns out, greatly accelerates one’s progress along the learning curve, and if one elects to learn in multihulls, this, too, is something more than style, for the revolutionary difference in sailing made by multihulls goes a long way toward offering a distinctive identity to the sailor. This, too, is something more than style. For me, it has been life itself.

Multihulls emerge in 1960’s California. Escape and survival motives, developing the Searunner series of ocean cruising trimarans for “seasteading.” Arthur Piver lost at sea. Stories of The Blowout Launching, Pops the Pagan Priest, The Broken Wing. Multihull mania in U.S., Europe and Down Under. Ocean racing begins. Countercultural conflict with yachting establishment intensifies.

The counter-cultural conflict between the early multihull devotees and the yachting establishment, as it initiated in this chapter, has since run its gamut. In the late 60s I was pelted with ice cubes at my own yacht club bar just for having one of those “anti-yachts.” Whereas, today there is evidence of “reverse discrimination” in the same setting; “We had a hard bash coming up from Monterey today, but of course I only have a monohull.”

The recreational sailing marketplace today is seriously depressed, but its multihull quadrant is on the “up side,” the only area showing signs of growth. New multihulls are very much in evidence in many marinas world wide, notably in Europe and the Caribbean where they sometimes predominate. At a recent in-the-water boat show at Annapolis, Maryland, I took the chance to climb to the third deck of a giant pleasure palace and look out upon the scene, and it appeared to me that about half of the floating exhibit was multihull. Certainly the longest lines for boarding were at the multis, especially at the big French “roomarans” whose luxurious interiors continue to astound “fender kickers.”

But at what cost? Today’s production cruising multihulls are so astronomically expensive that only the rich – or the charterers – can participate. Lamentable to me is that the can-do individualism of postwar culture, has declined, and it was that can-do which drove multihull owner-building. Many workaday people are no longer sufficiently confident of their jobs to commit to long-term, owner-builder, pay-as-you-go projects, and the “multihull identity” no longer imparts much exclusiveness, at least nothing like it did in the days when we were the “lunatic fringe.” membership in the multihull clubs is declining, not because there are fewer multihulls but because they are seen as just another boat. Oh well, I guess that was what we wanted fifty years ago when we thought multihulls were so obviously superior that they would take over the world in five…

So? That wave has subsided, but it gave us quite a ride. Now in the trough, we are still running at the same speed as the crests, and I wonder if the next white horse – surely developing right beneath us now – is going to send us “over the falls” and into some unimagined territory where multihulls sustain their owners rather than the other way around.

Family visits a prison. Making a multihull presentation to prisoners, then the family “escapes” to their boat and their ultimate freedom to go anywhere now. “Routine traverse” of Mexican seaboard, reception by officials in Guatemala, shooting Likin Bar, Browns leave their boat and move ashore while author recovers from hepatitis; an extremely fortunate interruption to his “providential” obsession.

Our “routine traverse” of Mexico’s western seaboard remains in memory as an absolute delight. I have been back to Mexico several times since, especially to Baja, where La Paz has the highest standard of living in the country, but when parting from friends there they say, “Pray for Mexico.”

The sad truth is that the poor place has been pretty well worked over since the Aztecs and the Spanish, yet the population burgeons to the point where many of the outlying communities are environmentally and economically non-viable, so people are forced to move to the cities. By some estimates the Capital, is destined by 2050 to host the largest concentration of humanity in the world. The US taxpayer has already bailed out the Mexican Peso more than once yet it continues a general decline.

All of western Mexico’s coastal coves and quaint villages, which we enjoyed visiting so much in SCRIMSHAW, have been developed into phantasmagorical resorts. Tourism is said to be their biggest industry, but of course it is actually drugs, drug trafficking and people trafficking. I am told that the pressure on our borders is nothing like what’s coming, and already the fence is unofficially allowed to “leak” enough people and enough drugs to keep Mexico afloat. I dearly love the place and its people, but it is clearly time to do something besides pray. In my view, this applies to the entire so-called developing world. It is developing, all right, but it simply cannot do what the developed world has done – the planet won’t allow. More on this below.

Living with Family in Highland Guatemala. Stories of the ancient Maya, their villages today, learning Spanish, and slowly acquiring the treasured feeling of belonging in the world. Textile quest, markets and festivals, a coffee craze. Coming to grips with the Third World double bind of poverty and population. Multihull events of the early 70’s. Returning to boat, getting out over Likin Bar, at sea again.

When heading south in SCRIMSHAW, our awareness of Mexico’s predicament actually did not manifest until the first of our two, eight-month visits to the next country south of Mexico and our favorite, Guatemala.

When gazing out upon the abandoned Mayan city of Tikal, twenty five square miles of metropolis buried in Yucatan jungle, I was forced to concede that this could happen to many of the world’s cities today. Going by the global escalation in our food prices, a general agribiz collapse, (such as beset the Classic Maya, seems at least possible. Then there’s the economy. Already we have seen the S&L crisis, and a banking meltdown, both illustrating the world wide tsunami effect of throwing mere pebbles in the pond. Then there’s Anthrax and all the other dread microbes around, to say nothing of Katrina and “…don’t drink the water, don’t breathe the air.”

Okay, so I’m bitch-bitch-bitching. We’ve heard it before and the sky hasn’t fallen yet, quite. I hope very much it doesn’t, but if we continue ravaging our farmland for making fuel (and billionaires)… Well?

Guatemala’s State of Peten, a vast territory that was once the Maya’s equivalent of our Iowa cornfields, had long since returned to jungle, until the 1970s when it was re-opened for settlement by the desperate hordes of ravine dwellers from the crumbling perimeters of Guatemala City. The Peten Jungle offered an effective safety valve for this population bloom, but thirty years of slash-and-burn subsistence farming has again made the Peten jungle vanish. Gone. Yet still the devout inhabitants are required to promise their God to procreate as much as is humanly possible.

I’ve been back to Guatemala recently, and find it still the most exotic country I have known, But I include it now with much of the “developing” world as being worthy of something more than prayer. Like, say for starters, universal access to the morning-after pill.

SCRIMSHAW’s Voyage from Guatemala to Panama. Fonseca Gulf, Costa Rica with other cruising boats, school on board, difficulties of raising two teenage boys on a small boat, Lobster overdose and shrimp overdose. Issues of getting drinking water and disposing of boat trash. Offering a leg up to a local. Bashing to windward in the Gulf of Panama. The captain as failed parent; father-son reconciliation.

Reacting to this, my favorite story of Volume 1, some readers have expressed surprise at my willingness to share the deeply personal relationship I have had with my sons, especially when we have sailed together. (There’s a similar story in Volume Two, Chapter 18.)

One criticism of the book has been its lack of such personal information about my relationship with Jo Anna. Well, really, that’s the point of the whole story. Without her guiding support of my boating conviction, there would be no story. We have been “sailing” in the same crew for 55 years at this writing, a life “style” which we are not necessarily recommending to others – it’s just the way we have chosen to live it.

Moreover, we even like each other, usually. We like our kids and they seem to like us. And when we don’t, it’s probably because I have said too much. Please accept, therefore, that no further remarks on this matter are forthcoming from me.

Running out of gas in the Panama Canal, Prison Island, The Zone: America’s experiment with socialism.” Outside the Zone. The San Blas Islands, Cartagena, overland to Ecuador, crossing Caribbean to Old Providence Island. After 18 years of living with that youthful promise (made here in Chapter 2), the author is finally absolved of his obsession.

Running out of gas in the Panama Canal, and being forced to sail through Gatun Lake dead against a piping wind, dodging tree stumps and freighter traffic, remains perhaps my finest yet most mortifying achievement as a mariner. It certainly was fun, but it was not an intended goal.

This story calls into question the very notion of goals. That personal promise to follow the sea, made to myself in Chapter 2, was healthy enough in itself, but I learned that such concrete decisions can result in requiring others to buy into one’s private trip. In my case it worked out, at least to the extent that my family bought-in willingly. When Jo Anna and I met, she, too, was searching for adventure, and our sons had little choice for they were well washed from birth. We, and our boats, were all lucky, but this is to concede that the freedom of seasteading is not as approachable now as it was last century. The maritime world has changed somewhat, including the economies, the populations, the intensity of competition and the declining resources everywhere all make it more necessary that the vagabonder have either marketable skills or ample wherewithal to ease the way today.

Nevertheless, there are more people “cruising” today than ever (although most of them with what can be properly called “style”), and there are still many untrammeled destinations especially for shoal draft vessels. I just hope it is still possible for an ordinary mortal, in a boat costing no more than an ordinary automobile, to achieve that special sailor’s sense of being able to go anywhere and “make it.”

SCRIMSHAW’s voyage from Old Providence to the Rio Dulce. Guidance from Captain John Bull, shooting Venus, rounding Cape Thank God. Life on the Great Sweet River: stories of getting stuck in a cave and smuggling booze by airplane. Heading home: the promise is kept but the author and family are left still “sailing through.”

The goal I reached at Old Providence Island was indeed intended, but it was reached only after eighteen years of chasing it, and under far different circumstances than I originally imagined. The promise made was so different from the promise kept

Then again, its eighteen years if you promise, and eighteen years if you don’t. Of course I’m glad I did it (what else can one say when it’s done? I just wish I had had some inkling, all those many years ago, of the inevitable contrast between the intended and the unintended, between resolve and resolved. Such an inkling would not have kept me home, but it might have helped me focus more upon the chase not the catch, the voyage not the destination.

Ah, but we did not miss out. We really did shoot Venus and round Cape Thank God. I really did get stuck in a cave and smuggle booze by aircraft, and all in the last chapter of just the first volume!

Having lived it now, I often think of Captain John Bull, ensconced in his pleasing little shack under the palms, reminiscing on his days as the skipper of the last trading schooner in the western Caribbean. I like to see him as yet another of my mentors, for here I sit, 40 years later, hunkered over my talking computer in this Virginia chicken house, reminiscing on my days among the multihulls. “Not too shabby, Abby,” I have just mumbled to my sleeping dog.

Forgivable?…

This is a non-apology for committing the shamelessly commercial ploy of leaving the reader hanging at the end of Volume 1, with the promise kept but the protagonist and his family still “sailing through.”

Here’s the alibi. Our publisher, Joe Farinaccio at Book Specs Publishing, thought it best if we divide this caper into two books. It makes the story accessible at a rock bottom initial price, and allows the reader to decide for himself about proceeding with Volume Two. Either way, we now make them both available as inexpensive downloads at www.outrigmedia.com, and we thank you very much for your readership.

0 Comments