Published in Multihulls Magazine, Nov-Dec 2009, pp. 60-65

by Michael Reddy – michael @ reddyworks.com

1 – Alive and Well at 39

On January 2nd, 2005, I drove towards the Nelson Sailing Center, in Toms River, New Jersey. It was Friday afternoon, and I was supposed to get checked out in a Bristol 30, in order to take some friends sailing on Barnegat Bay over the 4th of July weekend. As you drive down the hill there, you can see a portion of the yard. I noticed a small trimaran right up against the front fence. What went through my mind was a bit like this.

“Oh… Look… a small tri… I had one like that–what, 30 years ago I guess… I wonder who built her… what sort of shape she’s in… Boy… that’s kind of like the one I had… Must be a Piver design then… Hmmm… that’s actually a LOT like the one I had… Look at that outboard motor mount… God do I remember one just like that… What a—wait a minute!! Look at those mounts for the spinnaker winches. I built those!! Oh my God!! That’s Amistad!!”

As I got out of the car, and walked over to the boat, the feeling of disbelief gave way to recognition of the meaning of this event. First of all, back in the days when multihulls were anything but acceptable, this sleek little screamer opened the eyes of many a conventional sailor between New York and Boston. Secondly, she was constructed largely of quarter inch marine plywood, sheathed in a mostly very thin layer of fiberglass, using polyester (not epoxy) resins. Most such boats are gone. They delaminated and fell apart after a decade or so. Yet there she was, right before my eyes, probably just about to celebrate her 39th birthday!

I stood there for a minute, and then— impulsively—slammed my fist into the hull of the port ama. The deep, resonant BOOM filled my ears. Good Lord, she’s tight as a drum. And to be entirely honest, the sound brought tears to my eyes. Offshore, in the steep nasty seas of the North Atlantic—the terrible drumming of those three hulls became just more than I could handle.

2 — There’s History Here

I have promised the Nelsons, Gordon and Peter, that I would write down some of the history of this unusual boat. I have some pictures of her when she was first built, and so include them here. Gordon has promised, in return, to tell me who he bought her from. And I guess I intend to follow that lead up. What I know about, and will sketch here, covers roughly the first third of the trimaran’s life. But she’s in good shape now, and has been modified in various ways from her racing days—I wonder who did that?

3 – Bermuda and the ’68 OSTAR

Amistad was constructed, as I understand it, in 1966, by a sailor and boat-builder named Bernie Rodriguez. The photo shows the hulls under construction in his shop somewhere on Long Island, New York. Bernie was small in stature and limited in funds, so he collaborated with the designer, Arthur Piver, to scale down plans for the “Dart” trimaran from 36 to just under 26 feet. She was rigged as a sloop. Rodriguez knew there was some kind of monohull sloop called the “friendship class,” so he named her Amistad — which is Spanish for “friendship.” I suspect he was not aware of the already infamous slave ship with this same name. I’ve wondered at times what that “slavery” association might have meant in the larger picture of my life.

Now Arthur Piver, as you may know, was often referred to as the “Father of Trimarans.” He was the pioneering adventurer and back-yard boat-builder who first popularized this form of multihull in the Western world. Polynesians, after all, had been sailing them for thousands of years. “Anybody,” Piver claimed “could build these boats.” And since anybody did, many of the early ones fell apart. Again, as I understand it, the “Dart” was Piver’s last design. He was moving closer to the mainstream, selling certain plans now only to professionals, and getting just a little bit interested in ocean racing. Piver was lost at sea in one of his own boats not long after this collaboration with Rodriguez. His plans and many personal effects now form one of the collections at the Mariner’s Museum, in Newport News, Virginia ( see https://www.marinersmuseum.org/library/plans-drawings/ ). In any case, because of Piver’s alterations to the “Dart” design Amistad is a “one-off”—utterly unique.

The picture below shows Rodriguez sailing Amistad shortly after launching. The first Multihull Bermuda race ever was held in 1967. Rodriguez entered her and won. Unfortunately, he never spoke to me much about this race, so I don’t have many details. Did he singlehand, or take a crew-member? In 1968, Rodriguez sailed Amistad to England and entered the Observer Single-Handed Transatlantic Race (OSTAR). In talking to me about this, he described these passages, especially the race back, as harrowing experiences. Seaworthiness was not the issue. With high buoyancy floats, and a huge strength-to-weight ratio, Amistad is a very tough, fast, safe little yacht. But her “cabin space” is so tiny as to hardly deserve the name. What you go through offshore, trying to live, eat, sleep, and navigate in something like four by five by nine feet is almost beyond description (as I would later find out for myself). Again, if that little space were holding still, well, then–so it’s like a pup tent. But it’s not holding still. With such speed and such buoyancy, in too many conditions the soup will fly up out of your cup and spread itself across the ceiling. And you may need seat belts on the bunk in order to sleep. Anyway, Amistad and Rodriguez survived a hurricane that struck the fleet on the way to Newport. They finished 17th out of 43 in circumstances where a great many did not finish at all. Back in New York, after four significant offshore passages, Rodriquez had to sell the boat. He was again low on funds and had a boat-building business to attend to.

4 – Buying a White Elephant

If I remember correctly, I acquired Amistad around 1973 from a man named Ethan Wortis. After Rodriguez, before Wortis, there may also have been another owner. Ethan day-sailed the boat, mostly on the Little Peconic Bay, out between the Twin Forks of Long Island. As he described her, and I also initially perceived her, she was something of a white elephant. Out-designed by the slim, wave-piercing, low buoyancy floats of the Newicks and Crowthers and Kelsalls of the world, she could not be raced successfully and was too tiny to cruise. Only better-than-average sailors could handle her in a blow — and they were all busy with “serious” boats. So who would want her? Well I did. I wanted her pretty much the minute I saw her, bobbing around there, stern high, like some restless bird tethered to a mooring. At the right, you see Amistad on the dock at Greenport, Long Island, just after I had taken possession. That’s me, with the ‘70’s hair and beard. On the stern is a QME self steering rig.

At the time, I had been teaching for both Offshore and the New York Sailing School out of City Island, at the

Western end of Long Island Sound. I was good friends with two other instructors, Fred Hamburg and Richie Coar. Together, we did a lot of racing on MORC monohulls, attended Block Island Race Weeks, and the like. Initially “just for the fun of it,” we started to do to Amistad all the same things you did to campaign any MORC boat. I had Owen Torrey, known then as “the professor” at Ulmer Sails (now UK Halsey), design a genoa and spinnaker. We tuned rigging, looked for the best sheeting angles, built a rudder and centerboard with real NACA sections, faired the bottoms, and were rewarded with exciting day sails. I also discovered and joined the Long Island Multihull Association.

Just for the hell of it, I think in 1975, we got Amistad an IOMR rating and took her out to play around in the local, Eastchester Bay, Wednesday Night Race series. It was very interesting. With all the sheets, guys, and spinnaker halyard led back along the cabin top, and such a lovely broad walkway in front of the mast, two of us alone could easily do everything–even jibe the spinnaker. The big genny could be sheeted well outboard on beam reaches. The clew end of the sail did not have to curve back in to a narrow, monohull deck, where it seriously messed up the airfoil. Amistad simply flew on reaches. With a stiff headstay, a good boom vang, and the right sheeting angles — she was not bad to windward either.

But there was a problem. We often lost rudder control above 13 or 14 knots. The damned thing would cavitate. Suddenly there was a mush of bubbles at the stern of the boat and moving the tiller had no effect at all. I went to see Norm Cross, the designer who had inherited the multihull mantel from Arthur Piver on the West coast. “You need a shallow skeg,” he told me, “to fair the flow into the rudder. And get rid of that little balancing horn on the front. There’s no force on your tiller anyway.” Over the winter, I made these changes. They completely solved the problem. I notice now, looking at Amistad in the Nelson yard, that something curious has happened. The skeg is still there. But that little balancing horn is back on the front of the rudder.

As it became apparent that we were likely to win the Wednesday Night Series “going away,” Richie Coar and I decided to bite the bullet. I entered Amistad, the out-designed white elephant, in the Buzzard’s Bay Regatta, out of Marion Massachusetts. I had located Bernie Rodriguez himself, and invited him to crew with us. In late August, Richie and I set out to ferry the trimaran up the coast. Bernie was to meet us at the yacht club, on the morning of the first of three races. Now Amistad, in truth, has generated some amazing stories. I don’t want to get carried away and tell too many here. But I think you really ought to hear this one.

5 — Banging Up To Buzzards

The thing was, you see, I had never cared much about motoring little tri. The British Seagull outboard I had inherited from Wortis was designed to push a heavy displacement boat. Whereas the Mercury I bought later on zipped her along at 7 knots, the old Seagull simply topped out at 4, and was a misery to listen to. So, in the windless doldrums of August on Long Island Sound, Richie and I ended up well behind schedule. On the day before the first start, we found ourselves beating against the strong tides entering the Eastern end of Long Island Sound, into the teeth of a nasty, drizzling Northeaster. Plenty of wind now, but right on the nose. Still off Point Judith in mid afternoon, we realized the best we could hope for was to reach Newport and get some shelter for the night. A huge gloom descended.

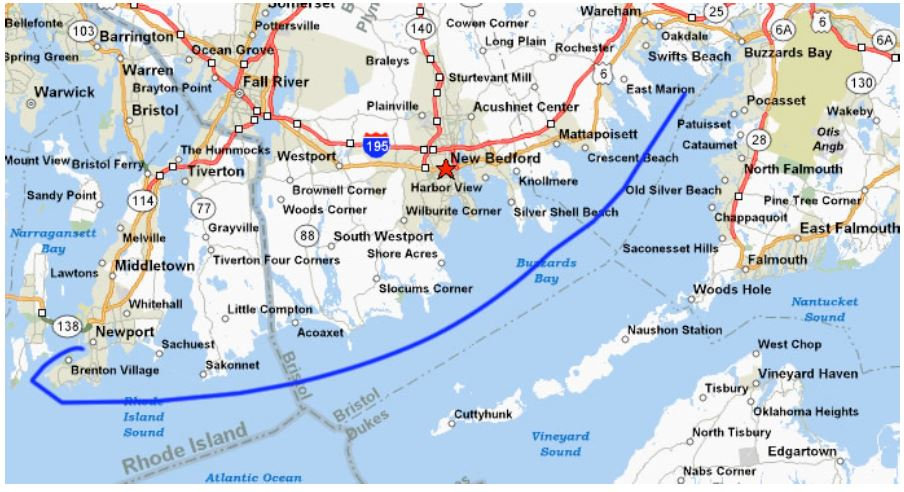

Finally picking up a mooring at the Ida Lewis Yacht Club around 8:30 PM, we went ashore for some hot food. “Too bad,” the launch boy said. “I’m driving up to Marion tomorrow to race a Shields. But you guys will never make a 10:30 start.” Back on the cold, wet trimaran, after dinner, I dialed up the marine forecast while Richie assembled the “spider bunk” in the bow. We called it that because there was so little room you almost had to hang from the ceiling while you assembled it underneath you. The announcer droned on about climatological data. I worked with the dividers on the chart. The starting line was about 45 miles to the Northeast of us. On the other hand, the announcer was saying the cold front that ended the storm would roll through Narragansett around dawn, with a stiff northwesterly filling in behind it. Was there a glimmer of hope? Well, likely not. But I set the alarm for 4:30 anyway.

When it went off, I stuck my head up through the companionway. The sky was clear, the wind indeed from the Northwest, but only 8 knots or so. Still, nothing ventured, nothing gained. I made coffee and started yelling every minute or so at Richie. The difficulty in waking him up at strange hours to go on watch was something of a legend among us. “Come on,” I said. “We’ll get out of the Bay, jibe around Brenton Point, and see if we can set the Chute. It can’t hurt to try.” 7 AM found us just past Lands End, looking at Sakonnet off the port bow. The wind was from the Northwest pushing up past 20 in the puffs. We debated setting the chute—or not. It was our only chance. But, at this point in our experience, we had never carried it on something near a beam reach in this much wind and sea. Plus which, the reach would get even closer after New Bedford. What if we broached with the spinnaker up? Would Amistad capsize? On the other hand, maybe there was just this tiny chance. Ah hell, let’s do it.

eaded way downwind, out to sea temporarily, to ease the apparent, and got the chute up. Then came the scary, thrilling moment as the two of us headed her back up, back on course again. Lord, she just took off. Thank god for the rudder fix. The old sum log speedometer had always pegged at 10 knots, and we were surfing easily at twice that. I watched waves and steered; Richie trimmed chute. As we survived more puffs and shifts in the wind direction, I felt a little better. But there would be no rest or pee breaks with this much sail up. It was focus, focus, focus. And we would have to move the pole forward and head up even more after New Bedford — so the worst might be yet to come. On the other hand, goodbye Sakonnet, hello Acoaxet, and there goes Cuttyhunk off the starboard beam.

In fact, Amistad taught us a great deal about her handling characteristics on this fateful day. And the first lesson came as I expected, after we put the pole almost on the headstay and headed up further to follow the curve of Buzzards Bay towards Marion. Because we did broach, not once but twice. The shore falls away off New Bedford, and you reach an area where the waves have 5 or 6 miles to build. I lost control there and guess what? Instead of lifting the main hull and flipping, she more or less water-skied sideways to a shuddering halt. Amistad’s floats are 150% buoyancy, “V” shaped, with a small chine just below the static waterline. So, going out of control sideways at high speed, mostly that leeward float just kind of planed until the boat stopped. The chute collapses of course, but you are not laid over on your beam ends. So you sheet everything out, head off until it fills and–bang, with a huge jolt you are off and surfing again. In the end, amazed and very excited, we blew in to the large gaggle of yachts around the starting line right around 10 o’clock. While runs like this have become somewhat commonplace in today’s world, 35 or so miles in 2 hours was then nearer to cutting edge.

6 — Sweeping The Regatta

But the surprises were not over. After getting our race circular from the committee boat, another multihull angles up beside us, people yelling and waving. Almost before we could wonder, “what’s this,” Bernie Rodriguez hops aboard. We said hello, repacked the chute, and set up for a spinnaker start. As we were entirely accustomed to doing in monohulls, we shot across the line a couple of seconds after the gun, and had the spinnaker up and drawing thirty seconds later. Hmm… nobody around… Was that NOT our start? Where are the other multihulls?

Well, in fact, they were there, and some of them were pretty famous. Heading the list was “Gulfstreamer,” the 60 foot Dick Newick trimaran (soon to capsize in the Atlantic), one or two of Newick’s smaller “Val’s,” and a Kelsall named “Azuleo.” One of the Vals, “Third Turtle,” had just finished 2nd in the 1978 OSTAR, and the other had come in 8th. These were very serious boats for their day. But, as we learned over the course of three days, something important was going on here. The multihull community at this time tended to view sails almost as afterthoughts. Any old rag of the right size will do. And races were things that covered thousands of miles and lasted days. Who cared if you were half an hour late for the start? Better to stay away from that crowded cluster of slow boats milling about the line until you had some room. Bernie Rodriguez on our boat accused Richie and I of being “string pullers,” and why didn’t we settle down and sail?

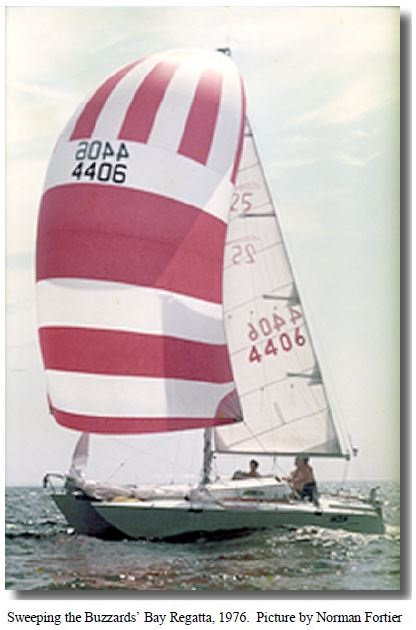

But he only said that on the first day. Because we won. Not only on corrected time (by the IOMR handicap rule), but also against most boats on elapsed time as well. Gulfstreamer herself only managed to pass us halfway through the last leg. And we won the next day, though by less. And we won the last day, though now only by a hair, and with a ripped seam high up on the old mainsail. The picture here shows me sitting in a daze in the cockpit after the last race, while Charles Chiodi of Multihulls Magazine takes my picture.

Amistad’s performance in this Buzzard’s Bay Regatta of 1975 became an object lesson about sail design and handling, deck layouts, and about timing and tactics in shorter, coastal races. Look how much better you could do if you paid attention to these things as well. By the third race, for example, there was a real multihull start, with everybody pushing for the line. In three seasons of racing Amistad, watching her take consistent firsts and seconds in all kinds of conditions, otherwise tuned in multihull skippers got the message. If you learned from the mainstream of monohull yacht racing, you could beat them at their own game.

Amistad was teaching us all and Richie and I especially were receptive learners. On one windward leg, we were keeping pace with several 30 foot monohulls, but falling slowly down on them. We were going to have to tack. I called Richie and Bernie in from their perch amidships on the windward float. But by the time we had set up for the tack, I noticed that we were now pointing at least as high as the monohulls. We didn’t need to tack. Amistad wanted more lateral surface area, and when we increased the angle of heel and accidentally gave it to her—pushing that leeward float into the water—it was worth 5 degrees at least. I knew then I would build skinny daggerboards into the floats. Owen Torrey had told me that wouldn’t help—but it did. And you see those things on all sorts of racing tris nowadays.

0 Comments