Summary

AMONG THE MULTIHULLS (CHAPTER 1) by JIM BROWN

Date happened: 1969>72

First chapter for Jim Brown’s memoir of modern multihull history and lore. Has many illustrations on our VIDEOS page or at our YouTube channel.

ABSTRACT

Chapter 1: To Build A Baby

Designing and building SCRIMSHAW, the author’s family boat, Walt Glaser’s Freudian meaning of boats. Drawing and selling the Searunner plans, the man-and- wife crew. Multihull events of late 60s. Writing Construction manual, launching SCRIMSHAW, collision with Commodore, ramming restaurant, Friends take over author’s blooming design business, Browns take off for Panama in SCRIMSHAW, a family crew with no destination and no plans to return.

Note: The following description is repeated from the Summary for the Foreword to this book. To see the Foreword itself,(two pages) clickFOREWORD

DESCRIPTION

Multihull pioneer Jim Brown, after fifty years of designing, building and seafaring in catamarans, trimarans and proas, here offers a brief Foreword to Volume One of his personal memoir. In two pages he describes modern multihulls as, “an entire new genus in the phylum of surface watercraft,” credits his declining eyesight for the visual multihull memories he calls “phantom visions,” and invites readers to participate in the OutRig! Project by telling their own multihull-related stories at this Site.

The focus of this two-volume work is on how the advent of modern multihulls has shaped the authors life and the lives of his colleagues, clients, shipmates and family. Volume One recounts multihull incidents and milestones from the 1940s to the 1970s, with a second volume in preparation covering from the ‘70s to the present. Brown identifies the cultural and geopolitical context from which modern multihulls emerged; explains the phases of their design, construction and application; and traces their progress from derision to acceptance in yachting, ocean racing, seasteading, and in commercial and military service.

Largely autobiographical, the book contains many sea stories of the author’s and his client’s escapades, mishaps and achievements. Brown relates the adventures of “seasteading” in foreign waters for years with his family, and then describes how, at age 76, his personal world view has been shaped by incidents in the books, and draws scenarios of what multihulls may mean to the future of humankind.

Multimedia coverage…

To see examples of the OutRig! multimedia presentation of “Among The Multihulls” and other productions, you may wish to visit the following links:

• As a free site launching special, the first three chapters of “Among The Multihulls” have been serialized here on OutRigMedia! To read Chapter 1, see the listing on the OutRigMedia!

• Extensive illustrations for each chapter (both stills and moving footage narrated by the author) will be posted on You Tube concurrent with the chapters serialized here, and you can also watch them on this website.

• This book has an introductory video titled “The Multihull Pioneers.” Featuring profiles of five early multihull trail blazers, it appears in two ten-minute segments on You Tube as listed on the Time Line. Watch the PIONEERS VIDEO on this site.

• The above video has a text counterpart. It is the original manuscript (before editing) of an article from WoodenBoat magazine titled “Multihull Pioneers.” It contains more detailed profiles of the same five early trail blazers featured in the video. This and other articles are listed on the Time Line, but you can click PIONEERS ARTICLE now (goes first to its Summary as with all Time Line listings).

• Text downloads and extensive on-line graphics for all the succeeding chapters of this book, and also the print edition of Volume One, will all be available soon. To express your interest in any of these please click INTERESTED.

…………….

Volume One

AMONG THE MULTIHULLS

A Memoir by Jim Brown

Chapter 1

TO BUILD A BABY

There we are, both of us ducking the smoke. A thick slab of chuck is broiling beside the fire, and the canyon is quiet except for the trill of the creek. Walter throws another redwood knot into the blaze, ashes fly, and he is covering his wine glass with the same hand that clutches it. I mumble something to myself about why I am building a boat, and Walter says, “A man doesn’t build a boat just to escape his reality, you know. He builds a boat to make up for the fact that he can’t build a baby.”

After my laughter and guffaws, in which Walt does not participate, he says, “A boat is the most life-like thing a man can produce with his own body. Its the most responsive to its environment and to its parent’s vane attempts at control. What else can a guy create that so closely simulates a living thing?”

In the bottom of Big Creek Canyon there was a small alluvial flat. It was only a hundred feet wide and about four hundred feet long, with the creek running on the north side against the steeper cleft side of the canyon. This made room for our two little houses and a tool shed. The buildings remained from a former Forest Service fire camp which Jo Anna and I rented from the beneficent McCrary brothers who owned the canyon and the local lumber mill. The only vehicular access to our home, unless one chose to ford the creek at low water, was by logging road. It descended through thick forest on the rubble side of the canyon, and made for all low gear both coming and going. It was now the dry season, so Walt had forded the creek.

The late Walt Glaser was a little-known but artful trimaran designer with an exotic mind. Sharp-featured and dark, he had a background of eight years “on the couch,” was a serious student of Freud, and often made his self-deprecating points with cynical humor. For instance, he called his series of trimaran designs “SALLY LIGHTFOOT, the only multihulls that stumble through the water.” Actually, I always thought his boats were salty and seamanlike. They would surely climb to windward, for they had nice big centerboards.

I had met Walt in the early sixties, and knew of his pioneering voyage to Hawaii and back in his somewhat-modified Piver 35-foot trimaran. It was now 1969, and I was intent on voyaging with my family in our own trimaran, one that I had designed myself and was slowly building in this canyon. Walter’s gift to “the “multihull movement,” and to me, was his grasp of the manner in which a boat, and especially boat building, fulfills the human male. He helped me realize that those early multihulls were not just vehicles; they were serving other, more cerebral human needs.

As I realize Walt is serious about gestational boatbuilding, my grin subsides. He continues, “You know how a woman is fulfilled by identifying herself as a mother? You know, sons or daughters, how many, how old, doing what? Well in the same way, a man seeks to identify himself as a….. Something! A father? That’s too easy, not creative enough. As a… What else? He has to fill in the blank.”

“Boats can do that?” I ask.

“Absolutely,” he replies. “We males are like the voice crying in the wilderness. We plead, ‘Here I am, please notice me.’ ‘I am a boating man.’ And the wilderness answers. That’s nice, but so what? There are lots of boating men.’ But If you fill in the blank with something like, ‘I am a multihull man,’ that puts a handle on you boy! The wilderness mumbles grudgingly, ‘Okay, multihulls are cool so you’re different. You realize of course that you’ll have to pay the price of being cool and different, but we of the wilderness do hereby notice you.’ Now! All at once you’ve got a straight pipeline to the most crucial facet of human development, your very own identity.”

Except for the growling noise of an occasional vehicle, there was constant music from the creek in our canyon. The creek-organist, according to her seasonal whims, varied the repertoire between trilling in summer and blaring in winter. The logging road continued up the canyon along the creek for a mile. It passed shallow pools with lurking rainbows in summer and spawning steelhead in spring. In winter one hiked past knee-high leafy mushrooms crawling with salamanders in their mating séance, rare albino redwood saplings sprouting from stumps, and little tributary creeks gurgling from deep beds of giant ferns.

A mile upstream the canyon terminated in a steep granite wall. On that wall a sinewy sixty-foot waterfall hissed into its pool below. Swimming there with my wife and kids, I could almost sense our mammalian heat being dispersed into bracing water which trees would drink, fish would breath and spiders would dance upon all the way to the Pacific coast about four miles downstream. And from there? Yes, I imagined something of our human taste would mingle into all the seas upon which we hoped one day to sail. But we were starting at the headwaters and had a long way to go to embarkation.

The sides of this canyon had been logged the first time in the late 1800’s, its prime redwood timber utilized to fire the boiler of the steam generator that first brought electrification to the Santa Cruz area. The stumps of those electrifying trees had rotted away leaving what looked like bomb craters. Around these voids grew offspring, each of a size that one could reach only half way around their trunks. These rings of redwoods had sprung from the root systems of their long-since assassinated forbears. These tight circles of trunks formed occasional atria throughout the forest.

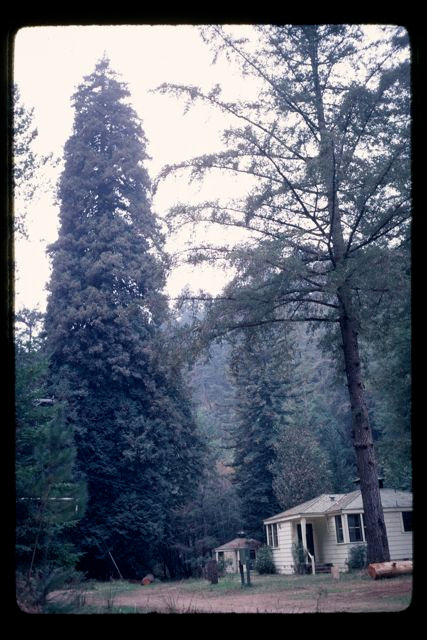

Our home during the construction of SCRIMSHAW, 1968>71, Big Creek Canyon near Santa Cruz, California.

However, these were but satellites, for in the center of the alluvial flat, right beside our home, stood two of the original monarchs that the loggers had saved, and these two made all other redwoods and firs now growing in the canyon look like houseplants. The pair stood so close together that a human could stand between them with outstretched arms, hands grasping the ridges and ruts of their hoary fireproof bark, and gaze straight up to see that no branches grew between the boles until their crowns. It was like gazing from the bottom of a 200-foot well. Furthermore, the lower branches of this pair, themselves of saw log size, sprang outward from the twin columns to arch downward and form a grand boreal grotto. About thirty feet high and seventy feet wide, this vault was open at all sides, and on the ground a few fir logs lay as peripheral pews. The fire pit, a rough circle of rocks, comprised the central alter for this cathedral-in-the-round. It was in this monument that we regularly worshiped – in our own way – the sacrament of family and friends in Eden.

It is autumn, so the creek is well down into its banks. Lacking floods in recent years, the watercourse has become choked with weedy alders, which further muffle its gurgling. While pondering the insight that Walt has shared, I notice that except for the occasional squeals from our kids and yelps from our dogs, who are all busy damming a swimming hole, there is little activity in the canyon. The campfire snaps occasionally, and the thick chuck roast, smeared with mustard and herbs, roasts beside the flames sizzling invitingly. Walter goes on:

“And talk about identity! How about being a pioneer? We’ve always known we are sailing virgin water with these boats. Building a multihull is like having a kid that you know is going to grow up to be president. The potential of these boats is enormous. They are definitely going to affect the future of seafaring, and we know it. Not everybody does, but we do.”

“How do we know?” I ask.

“Because we’ve been to sea in them. We’ve seen for ourselves how inherently right they are. How they let you make mistakes and get away with it, how they can slash to windward and surf downwind and ride at anchor like a duck and slide in onto the beach just for the fun of it. And how they thrill the sailor right down at the pit of the pituitary. And most of all, how they tell us who we are. We’re pioneers in something that’s wide open, that’s unregulated, and that is so free and off-the-wall that you can see directly the results of your own efforts and decisions, good or bad! And what you see is something never seen before. That’s rare these days. It’s exciting. It’s irresistible.”

“How do you mean ‘irresistible,’” I ask.

Well, you see it every time someone buys a set of plans. You are offering them a means to enter the fraternity where anything is possible. You offer them the speed to show their heels to the establishment, the power to escape normality, to go anywhere, to see the world. What red-blooded identity seeker can resist that?”

Thinking back today I must have found Walt’s insights a revelation, for I never again doubted that I was offering something worthwhile to my clients. No longer did I feel like a phony, capitalizing on the feats of others and the hysteria of the times. In our brochures and slide shows, I began to shape my message in terms of escape, survival, freedom and identity.

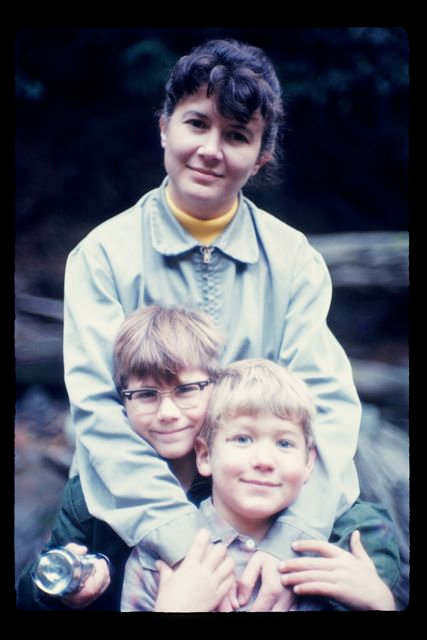

Jo Anna with Steven (left) and Russell at about the time we began building SCRIMSHAW.

SCRIMSHAW…

It worked, for my wife Jo Anna and I soon found ourselves to be, for the first time in our married lives, some seven hundred dollars in the black. With this exceptional asset, we began to build our own boat. I fixed up the little tool shed on the place as a shop, finished the plans for the 31-foot Searunner trimaran, and started cutting its frames. It was the most gratifying work I had ever undertaken, but I had no idea it would be three and a half long years before SCRIMSHAW would be borne upon the water.

Anyone who says a boat project will break up a happy home should consider the overall fragility of that marriage and find another factor on which to place the blame. No doubt a boat will test a good marriage, as it has ours for the last thirty seven years (yes, at this writing in 2010 we still have SCRIMSHAW), but she also has been a prime ingredient in the adhesive that has held us together as a family. What is that ingredient? It was blind luck, providence. Fifty years ago I happened on a woman who was looking for authentic adventure, and who was willing to buy into my trip. Jo Anna’s unflagging support of my boating binge has allowed the boat to make an essential difference in our family lives, and after a half century of marriage we still sail in the same crew.

And the kids? Our two sons Steven and Russell (then sub teens but now in their late forties) were camping overnight in the upside-down hull before it was even planked. They were too small to help much in the construction, but watching me work drew them into the shop where they insisted on using the tools in their own projects. Allowing them to do so seems now to be the only vocational thing I ever gave them, for today they are both professional multihull designers, builders and sailors in their own rights.

But finishing the boat was a serious challenge. The multihull anatomy is complex, and despite the simplicity of the tools and skills required to build such a structure out of plywood, lumber and glue, the task seems at times interminable. There are three hulls to build, you have to join them all together somehow (and building that platform is like building yet another hull!), and then there’s the hardware, mast, rigging, sails, plumbing, wiring, controls and – most daunting – all the sanding, fiberglassing, painting and finishing inside and out. It really takes time, money and commitment.

During the years I was learning of this commitment, action on the multihull scene was becoming increasingly frantic. It was the late 1960’s, so the anti-war movement was getting nasty, as were the government scandals and the body bags. Catamarans, trimarans and ferro-concrete monohulls were popping up and popping out of back yards and boat builder’s communes all over the country but especially in California. Many were built in the hinterland and trucked to the sea or to rivers for journeys to the coasts. Jo Anna and I were selling plans enough to support ourselves and our SCRIMSHAW habit.

Building her was an addiction. I kept drawing plans and giving talks to the multihull clubs in Seattle, San Francisco, Los Angeles and New York, but the boat tantalized me at the same time. It was my respite from swimming non-stop in the multihull maelstrom. With the phone ringing constantly, the mail pouring in with questions to be answered, and uninvited drop-ins continually finding their way down our logging road just to listen to the horse’s mouth, I was not able to spend much time on our boat for the first two years or so, but her skeleton slowly took shape in the canyon.

Pre-cutting the plywood panels in preparation for the “planking party.”

Pre-cutting the plywood panels in preparation for the “planking party.”

We had lots of client/friends; many of them were building our boats under similar circumstances; make a living and make a boat at the same time. We developed a system of “planking parties,” like the old barn raisings wherein one builder would get as much done as possible by himself, like cutting and fitting all the plywood planking for his hulls, and then call in the cohorts to apply the planks in a boisterous weekend. We shared in these occasions with our particular friends Patti and Jerry DesRoches, Barbara and Jim McCaig and Tom and Blanche Freeman, all building Brown-designed trimarans in the vicinity. The guys would almost throw the panels at the boat as one man with a pneumatic staple gun would bang them home; inside the upturned hull the ladies wiped up excess glue, their hair protected with bandannas to prevent contamination from wet Weldwood®. After a day of such frenzy there would be the usual pot luck feed and partying. Kids and dogs and home-made music augmented these scenes. Folk songs and folksy camaraderie would continue well into the night. At our place, dawn would find a ring of twitching sleeping bags around the smoldering campfire in the redwood cathedral. Coffee and a hearty breakfast would crank things up, and off we’d go for another day of communal construction.

Steven hams it up for the camera during the planking party.

Steven hams it up for the camera during the planking party.

The planking crew after a long day, with a hard day’s night in store.

The planking crew after a long day, with a hard day’s night in store.

The crew sings The Beetles favorites around the campfire.

The crew sings The Beetles favorites around the campfire.

It was heady stuff for us all, but especially for me, I think, because I was the one who had drawn the plans for these projects. The pressures of this responsibility were offset by excitement and anticipation of setting off to sea. I was taking the whole trip, beginning with design, then construction, and then – I was certain – to seafaring with a family crew. It was wonderfully complete except that we would learn that building was, by itself, no preparation for ocean sailing.

Furthermore, I was sometimes dismayed by building from my own plans. I actually followed them closely; as did most of my clients, but at times I had real difficulty understanding the drawings. I had built the boat completely in my head while producing the drawings, which were acknowledged as being among the most expressive and comprehensive available. The pictorials showed two or three views of every component in the structure, and they were surrounded by little notes to guide the neophyte builder, but every so often I would read one of those notes and say out loud, “Now what in hell does he mean by that?” This dismay helped me realize that plans drawn for neophyte builders need to be accompanied by extensive consulting services, and I had created a monster that was going to starve without my ongoing personal involvement. How could we ever get away?

Sailing Through Space…

While the boat was taking shape, our boys were growing up and our business was budding out, and all in a glorious setting! There were many occasions when we pondered the natural splendor of a lively creek in a redwood canyon near the California coast. One such occasion was the lunar eclipse of 1971. Of the many attempts made by people to witness celestial events undiminished by artificial light, say, from aircraft or mountain tops or isolated islands, I herewith suggest trying from the bottom of a box canyon. Something happens there at night that must be similar to the strange phenomenon of being able to see stars in daylight from the bottom of a well. Our canyon walls blocked off the metropolitan lumes of San Francisco, San Jose and Santa Cruz giving minimal skylight on the night of the eclipse. Fortunately the central coast was flushed with cold, dry air fresh in from the Aleutians.

We were joined that night by some valued non-boating friends, folks with whom we could socialize without talking shop. Bruce and Marcia McDougal, operated a nearby ceramic school, and Bruce Bratten was a venerated local roustabout. The five of us often packed away enough of the local varietal wines to float our boat, but this night we soberly assumed a vantage on the moon from the bottom of a big hole. The vista began with the man in the moon assuming his usual countenance as a far off face on a dime in a spotlight, but slowly the vista developed into a shocking celestial show that is often re-run in my theater-of-the Big Blind Blotch:

His radiant face is set in a canyon-rim frame that is bordered by the silhouettes of coniferous spires. He slowly slides into the partial shadow of Earth’s atmosphere to be tinged on one cheek by spectral hues of blue. While growing apparently much larger he is shaded by Earth herself and thereby overwhelmed by sunset red and becomes startlingly globular. Huge now, we sense nonetheless that he is a mere bonbon orbiting our bowling ball, yet he comes so very close we fear a stellar smashup.

As we shiver there in the canyon spellbound by this sight, we reach up, stretching as if confident of feeling the old man’s blotches and zits, of rubbing the wrinkles that are casting shadows all around the edges of his spherical face.

Beyond this nearby blushing ball we see the heavens, too, in three dimensions; actually perceive their – until now – unfathomable .depths. Considering two planets as neighbors in our own sun’s light, we then perceive the stars as hugely distant suns, not tiny moons. This foreshortened projection of the moon makes the rest of what’s out there – Milky Way and all – stunningly deep. We at last apprehend the enormity of our isolation in this place called space.

Then, as if by time reversal, one cheek of the otherwise red-faced man in the moon is tinged with celestial blue. He now rapidly recedes, pales, and recovers his usual countenance as a far-off dime in a spotlight. We are left cold, awed, enlightened and a little frightened. Do we really want to know how utterly alone we are on Earth?

That night’s peculiar portrait of the heavens has stayed with me for reasons of its parallel with seafaring. Our project of building SCRIMSHAW was somehow akin to whacking out a space ship for traveling in the most vast wilderness still accessible to individuals. We became nothing more than cosmic mites now conscious of our inconsequence. Marooned on our mass of molten magma, which is skinned over by a rusty crust and two-thirds smeared with water, our intent was to go, and come to know, something of this smear, this hydrosphere, for it is apparently unique upon our Earth, not so far found upon any of the other orbs in multiverse.

Like reaching up to touch the moon, the very notion of embarking on such an odyssey was scary. We became audacious to ourselves. Marooned here on a particle of stardust, we were contemplating the investigation of Earth’s mid region, that frontier where its wet smear mingles with its lithosphere. We knew it had been done by families before; cruising with kids was not unique. It had started with the ancients of Pacific Oceania who moved the makings of entire villages from one island to another very far away; their equivalent of colonizing space. But could we do it? Ordinary gringos in a back yard-built bucket? Well, we were readying to try.

Print Power…

During the sixties the west coast multihull owner-builder scene was dominated by trimarans (although the catamaran would later prevail in popularity), and several small magazines popped up. These included TRIMARAN, TRIMARANER and TRIMARAN SAILING. They survived only briefly but gave the movement an air of legitimacy when it was badly needed.

I wrote occasionally for these publications, espousing the notion of “seasteading,” a life style wherein a vessel’s crew – especially a family crew – could be sustained by, with, and from their boat.

Scrimshaw SCRIMSHAW soon after launching in June, 1972.

Scrimshaw SCRIMSHAW soon after launching in June, 1972.

It was being done, and not just in multihulls, by a few very resourceful and dedicated cruisers. Some sailed to foreign lands and settled in harbors where they had skills that could be sold ashore. Some chartered their boats to tourists, and others operated small businesses from on board such as making canvass work for other boats. They lived frugally but often very much enjoyed their endeavors. In my writing I emphasized safety, discouraged racing and tried hard to identify the purpose of my boats as for something more than showing off.

In 1968, Jo Anna and I published a slick catalog of Searunner designs. In the Catalog I again espoused the notion of seasteading, asserting that the boats were intended for the purpose. Soon we had the great good fortune to have our catalog briefly reviewed in The Whole Earth Catalog, and all of a sudden our plans sales increased substantially. Once finished, the cost of printing and mailing plans was small compared to their price, so finally all that eyeball-busting work was paying off.

We had been duplicating a set of leaflets to accompany the plans which guided our builders during construction. Nevertheless, phone calls, letters and uninvited drop-ins were taking over our lives, leaving little time for drawing new plans or working on our boat. As SCRIMSHAW slowly took shape it became obvious that we were never going to be able to extricate ourselves from our clientele without something that really answered all (almost all) of the questions. Furthermore our customers deserved more information, enough to get them through the seemingly interminable, truly complex, commitments they were making to our line of so-called Searunner Trimarans. So, with Jo Anna typing the manuscript, I began to try to write it all down, every scrap of know-how I had mustered from my schooner days and as a beginning builder making several of these boats, and counseling neophyte builders for almost fifteen years. I took a lot of pictures while building our boat and of others, nitty-gritty details of all kinds. I mined my own drawings for examples of typical practice, and wrote reams of how-to, trying hard to avoid the usual deadening gobbledygook of technical writing.

To this end I was mightily assisted by Jo Hudson, whose cartoon illustrations became icons in our publications, for they served to take the drudgery out of boatbuilding and the fear out of seafaring. Without Jo’s cartoons, the Searunner lineup would have been just another also-ran.

When SCRIMSHAW, yet to be named reached the stage of three hulls completed and the main interiors roughed-in, it was time to move her parts and pieces out of the canyon to a place where she could later be transported to the water as a unit. This exodus involved not only moving out of our beloved canyon home but also borrowing a rickety truck and trailer for towing the boat over logging roads. Hauling the main hull first, son Steven and I came out of the woods only to have a breakdown on a narrow curve of the Coast Highway with no shoulder. We were rescued by Bruce Bratten driving a school bus; he towed us, the truck, trailer and main hull out of peril. We were then escorted through Santa Cruz by a red Cadillac convertible driven by the midget whose profession was to speak the voice of Donald Duck. The Caddie was piled high with hippies (friends of those who loaned me the truck and trailer) who dutifully blocked traffic at every intersection – regardless of the lights – while the midget excoriated those who objected to the blockage as a vociferous, angry and profane little duck. I remember thinking that this was probably the most hazardous voyage the boat would ever make.

We moved into a grand house near the center of Santa Cruz and settled Scrimshaw’s components into a boat yard just blocks from the harbor with its four-lane launching ramp. We were really selling plans now, enough to start salting away a cruising fund, but the need for a real Construction Manual became increasingly evident. I worked on the boat when the weather permitted (she was never under cover) and when it rained I worked on the Manual. We were making progress, but there seemed to be just too much to do! Jo Anna and I knew that if we were ever going to take a big deal boat ride with our sons, we were going to have to go soon; otherwise they would become involved with their peers and not want to leave.

Yet we were committed to leaving! Why? On the face of it there was no reason whatever. We had a great place to live, a promising future, lots of friends, two great kids and two great dogs. Yet the call to adventure, to sailing and to escape was irresistible. After all, I was sending hundreds of people – many as families – out to sea in my designs in the same nebulous quest, and it seemed only fair that I should subject myself and my family to the same treatment. In order to get away we were even prepared to simply shut the business down and flee.

The Deal of a Lifetime…

In early 1971 I was approached by friend Tom Freeman with a proposition. He and John Marples had been talking, and now offered to run our plans business for us while we went cruising. They were already conducting ALMAR, an active procurement service for boatbuilders, selling spars, sails and a host of yachting equipment to back yard builders of all boats. Some of this equipment was manufactured by Marples and friends at the boat builder’s collective in Alviso, an abandoned and sometimes-flooded cannery town at the very southern end of San Francisco Bay. There were all kinds of cruising craft under construction by owner-builders, including several Searunners, at this vibrant site. Couples and families with building projects there either hauled in house trailers or whacked out shelters in the cannery buildings, some of these habitations accessed only by high ladders to cliff dwellings scabbed into the giant trusses of the old industrial sheds. Colored lights, cool music, holistic food and the air of incense typified these residences. Working at outside day jobs and waling away on their boats late into the night, these builders often helped each other, exchanged vital information and sometimes partied hard. The morning after one such party I awoke in an aerie pad to discover, while descending the seemingly endless ladder to the ground, that some wag had inscribed the lofty wall with a spray can to read, “Jim Brown slept here.” I had arrived!

ALMAR was the source of a non-yachty line of marine hardware designed and built by John Marples expressly for Searunners. The line included running backstay levers, robust lifeline stanchions and the now rare and highly coveted aluminum winch handles whose castings were boldly inscribed, “MADE IN ALVISO BY HIPPIES.” ALMAR’s stuff sold well and served well, and it seemed appropriate that this progressive outfit should purvey plans for Searunners.

So we made a deal: Tom and John would handle our plans and consult for the builders, and we would split the gross income fifty-fifty. Starting immediately! The only hooker was that if I was going to bail out, they must have a definitive construction manual to answer most of the questions being asked by our builders.

All at once I had time! In a great spurt of activity we produced a big book called SEARUNNER CONSTRUCTION. I wrote furiously by hand from down on the beach, Jo Anna typed the camera-ready text on our new Selectric typewriter in our kitchen, Jo Hudson drew the cartoons at his mountainside home in Big Sur, Tom Freeman did the paste-up composition in our basement, and – gambling our entire cruising fund of some ten thousand dollars – we had the book printed up in Berkeley. Now long out of print (but destined for re-publication soon), the book developed a cult following and was used by many builders of non-Searunners. Even builders who wanted boats other than Searunners built Searunners because of the book. I now regard that project as the favorite undertaking with our friends and, what’s more, our arrangement with Tom and John allowed Jo Anna and me to take three years off at age forty! It was literally the deal of a lifetime.)

But For the Corks…

Now, at last, I could finish the boat! For ten months in 1971-2 I worked almost full time on SCRIMSHAW, loving it but hating the rush. We were committed to setting sail in the summer of 72 while the boys were eleven and twelve, believing strongly that if we didn’t go NOW we would never get away. We set a drop-dead launch date of June 21st, the summer solstice. Despite the endless details of trying to finish a seagoing sailboat, ready to sail before the launching, we somehow made the date.

Early on that morning I backed our station wagon, loaded with equipment for the boat and supplies for the launching party, into my workspace. This was a maneuver I had performed many times, and I was preoccupied with planning the launching, but while backing up I was surprised by a commotion behind the car and saw a ghostly figure – someone wrapped in clear plastic – roll out from almost beneath my back wheels. It turned out to be a local boat bum sleeping off a bender. We were both shaken by the near thing, but he then noticed a carton of fresh orange juice, left for him in the plastic by his ultra-considerate girl friend of the previous night. He calmly offered me a swig, and we toasted the start of SCRIMSHAW’s launching day together.

Then I noticed that the boat and the outer walls of the shop building were all plastered with poster-sized pictures of me making a panic face. I knew Tiny Tommy Freeman (6-4 and 260) had been working that night on his printing press, and that this was going to be a lively day.

The move to the launching ramp went well, and so did the christening. In accord with a local, cliquish tradition at multihull launchings, we anointed the rudder with some “sacred wine” saved by friends Patti and Jerry from their rounding of Point Conception in their Nugget trimaran with a broken rudder years before. Jerry had dragged the wine astern in crashing waves, the plastic jugs serving as a movable drogue. He swung it from one side of the boat to the other to steer finally into shelter. This was our christening; we saved the cases of Champaign for another purpose.

As the boat and trailer descended the ramp, all the kids in the party wanted to ride the vessel into the water. Thinking that this really was a family project and wanting to begin by delegating responsibility to our young crew, I agreed to put them all aboard for the launch. But I instructed Steven and Russell, “As soon as she floats free from the trailer I want you guys to go below and look for leaks, okay?” Brimming with a sense of duty, they agreed.

So into her element she rolled… And came afloat! I’ll never forget the moment, or the sound of the cheers.

Nor the moment after when Steve, the elder of our two, popped out of the forward hatch to say solemnly, “Dad, the water’s coming in.”

“Sure Steve,” I replied laughing. “Cry wolf and nice try.”

“No Dad, the water’s coming in fast.”

Chagrined, I waded in up to my chest to the bow and, with an effort I could never duplicate, climbed aboard dripping and draining. I jumped to the hatch and saw that Russ was working the bilge pump and two other youngsters were deep in the holds beside the centerboard trunk, each with his thumb stuck into one of the centerboard glands to stem the garden hose-sized streams that both fittings had been squirting into the bilge. I had left the caps off of these fittings.

Meanwhile the crowd had pulled the vessel over to a floating dock. Amidst the apprehension and merrymaking on the dock I confided to Jo Anna, “I left the caps off of the centerboard gland and can’t find them. The kids have the leaks under control with their thumbs, but they’re turning blue and I don’t know what to do.”

Jo Anna then reached into her purse and slowly extracted a small plastic bag filled with an assortment of corks. “Will these work?” she asked. “I saw them somewhere and thought they might come in handy.” What a first mate!

With my glands firmly corked, we went on with the party, which grew to such proportions as to cause the floating dock to sink, soaking several participants. Tipsy and enthralled, we moved aboard that day and spent the next three years living in, with and from the boat.

But again, our beginning experiences with her were not auspicious. On our first sea trial we were just leaving the dock, close hauled against zephyrs moving slowly down the fairway in the harbor when a proud monohull about our size slid out of a side isle right in front of us. With no recourse but to turn and collide with another boat on an end tie, I chose instead to ram the intruder with a bang. SCRIMSHAW was undamaged but the teak toe rail of her opponent was smashed, and of course the boat was owned and steered by the commodore of the Santa Cruz Yacht Club. How to start out, eh?

Our next foible occurred at the end of our first hop to another harbor. Upon entering between the breakwaters at Moss Landing, after a rousing sail from Santa Cruz in a stiff breeze, we found that our diminutive outboard motor, of only four horsepower, was insufficient to push us against the wind up to the awaiting slips. As we were being blown out of the channel I dropped the anchor, which at once became fouled in a mass of weed, and we drifted helplessly sideways until ramming a waterside restaurant. The patrons watched us coming in wonderment until the collision shook their tables and sent them scurrying. Again, there was no damage and no blood, but my pride was weeping.

Doggedly, Jo Anna and the boys stuck with me and I stuck with the plan. In the wee hours I sometimes fretted about the wisdom of that plan, the intrusion on our lives and the risk of seagoing in a back-yard boat with a family crew. Was this commitment reasonable? We would find out.

By late August we had either sold or given away everything we owned that did not belong on the boat. Tom and John were running our business well, and our other friends became convinced that we really were going to leave… With no idea where we were headed and with no intention to return. The boys were game, and we wanted out of our involvements ashore. We wanted to be away from California’s cultural craziness of the time, away from the bombardment of bad news about the economy, the government and the Viet Nam War. We wanted into the seasteading adventure

When I say “we” I mean all of us. We could only fantasize the enormous change in our lives now beginning, and of course we all had apprehensions. Yes, Jo Anna and I had done this before in 1959 with our little trimaran JUANA, a junket that lasted only three months (Chapte4), and I had been bitten by the seafaring adventure in my premarital schooner-bumming days (Chapter 2), but now we were a family! The boys were leaving their peers, I was leaving my career, and Jo Anna was uprooting her progeny. We were quite possibly venturing into harm’s way, and we had no clear destination, no notion of the long term consequences of bailing out and sailing away.

The enticement to go, however, was irresistible. By now we already knew something about the seakeeping properties of modern multihulls, and we knew that the thing about adventure was that it could be a whole lot easier to stay home. But after eighteen years of trying to get my affairs in order, I was finally headed back to my beloved Caribbean. This time we had a real boat under us, and after ten years of driving our own business together we were not broke and Jo Anna was not – as she had been the first time we left in 1959 – pregnant! It all combined to suggest great portent. Surely our very own Shangri La was lurking somewhere over the horizon, and this was our chance to find it. Quite frankly we were scared, but we were also greedy to go.

Greed versus Fear…

It is mid August 1972, the night before departure. Steve and Russ are snuggled in their forward cabin bunks after a very hectic day. Jo Anna and I are basking in the lamplight of our sterncastle, sharing the last swigs from the last bottle of Champaign saved from our launching party six weeks previous. Jo Anna, a pathological reader of literally everything from the classics to license plates and cereal boxes, is thumbing the pages of one of the boys’ comic books. “This is too much,” she mumbles.

I, a pathological drifter through the life of the mind, am pondering the seemingly endless sequence of events that has brought us finally to the point of embarkation. How is it, really, that I have so doggedly dragged myself and many others to the brink of a precipice from which we must either soar or sink? Why is it? My thought turns to a promise formed for myself in the light of another lamp in another cabin long ago, and I mumble, “This time I have a mate,” but Jo Anna is clutching the comic with both hands, focused. Still, I am feeling pleased by being not alone, and I ponder the chances of finding a woman – to say nothing of two sons – willing to share with me this perch on this precipice.

My reverie is crashed, however, when Jo Anna suddenly slaps the table and exclaims, “That’s it! That’s how I feel!” Chuckling, she tries to read out loud from the “comic” story of some fictional gems. I get the gist that there is a certain clutch of emeralds which carry a curse for all who possess or try to steal them. This includes the currently aspiring thief, a character named Gryce. As the conclusion of this month’s installment nears Jo Anna laughs and then, speaking through her giggles, quotes the final passage:

“Many men had died from coveting those emerald orbs, but Vincent Gryce’s greed was greater than his fear.”

“That’s exactly how I feel!” She laughs again and says, “My greed is greater than my fear!”

The crew of SCRIMSHAW, 2009. Left to right: Jo Anna, Russell, Jim (in hat), Steven. Credit: Ashlyn Ecelberger

The crew of SCRIMSHAW, 2009. Left to right: Jo Anna, Russell, Jim (in hat), Steven. Credit: Ashlyn Ecelberger

End chapter 1

Illustrations for this chapter, including some moving footage, all with detailed, captions narrated by the author, are available at this website.

0 Comments